The word

“cryptoscatology” refers not just to conspiracy theories, but to any field of

endeavor that’s considered by mainstream culture to be transient, peripheral or

hopelessly obscure. Today I’m shining a

spotlight on two recent works of non-conspiratorial cryptoscatology that are

noteworthy for the similarities between the authors’ individual prose styles

and research methods, namely an obsessive attention to ostensibly insignificant

historical factoids and data that—when joined together and seen as a whole—form

a much more complex and vivid picture of the subject matter at hand.

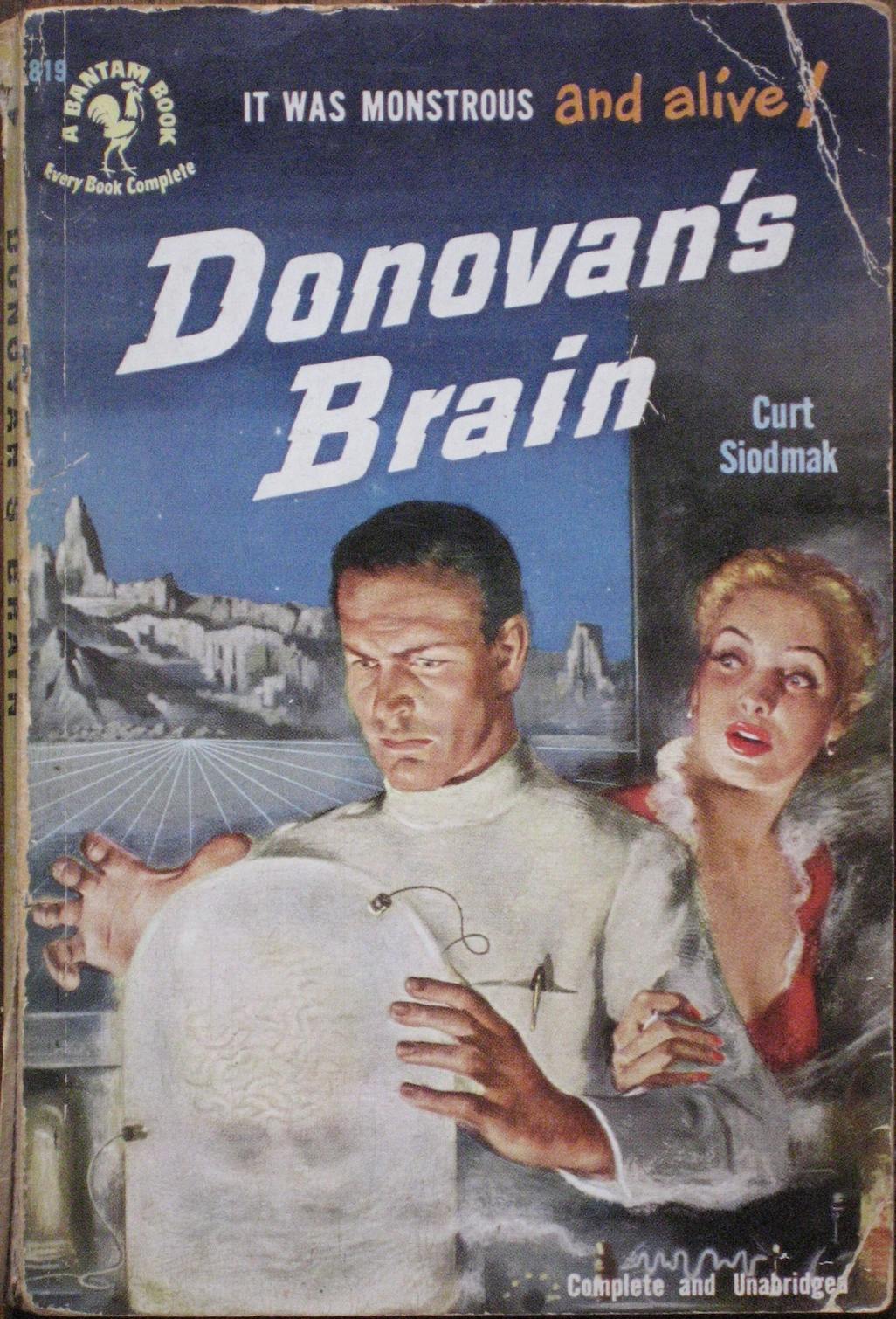

The first book under

discussion is Gary D. Rhodes’ THE PERILS OF MOVIEGOING IN AMERICA (Continuum,

2012), an exhaustive and yet highly entertaining history of America’s

tumultuous relationship with the cinema, which carefully walks an impressive

tightrope act between meticulous, academic scholarship and highly readable

prose. Perils reminds me of one of my favorite non-fiction books, Herbert Asbury’s The Gangs of New York (1927), in the sense that the book

paints a detailed picture of an era that’s so distant from us now that it

almost seems like a piece of outlandish fiction.

The description on the back of the book reads: “During the first fifty years of the American

cinema, the act of going to the movies was a risky process, fraught with a

number of possible physical and moral dangers.

Film fires were rampant, claiming many lives, as were movie theatre

robberies, which became particularly common during the Great Depression. Audiences also confronted an array of

perceived moral dangers. Blue Laws

prohibited Sunday film screenings, though theatres ignored them in many areas,

sometimes resulting in the arrests of entire audiences. The Perils of Moviegoing in America: 1896-1950 provides the first history of

the many threats that faced film audiences, threats which claimed hundreds, if

not thousands, of lives.”

On the back of the book is also a blurb by Charles Musser,

author of The Emergence of American

Cinema, calling Perils a “page

turner,” and in an odd way Musser is absolutely correct. Perils

reads like an eccentric novel in which the protagonists are the ghosts of

long-dead movies theatres. There are images in the book that are as

haunting as anything one is likely to read in a popular supernatural

novel. Early on, in the introduction,

we’re treated to this heavily symbolic—and yet real—image describing the inside

of a movie theatre called the Knickerbocker that had been wiped out by a sudden

cave-in due to poor building construction:

Laughter filled the auditorium

during Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford (1921) until a “roar like

thunder” transformed the screening into a tragedy. Two feet of snow proved more than the

theatre’s roof could bear. When it gave

way, steel, concrete and wood rained down onto the audience. The newly added weight on the balcony caused

it to collapse as well […]. Screams from

a “tangled mass” greeted rescuers. They

worked through the night to move over 100 injured moviegoers to nearby

hospitals and makeshift infirmaries.

They also discovered body after body.

Four of the corpses sat upright in their seats, as if they were still

watching the film.

That last line sets the tone for the rest of the book.

It’s a disturbing, almost surreal image that lingers in the mind long

after the book is closed.

In March of 1931, Charles Fort wrote the following response

to a positive review of his book LO!:

Something that you see in LO! is that it is a kind of

non-fictional fiction, or that, though concerned with entomological and

astronomical matters, and so on, it is “thrilling” and “melodramatic.” I have a

theory that the moving pictures will pretty nearly drive out the novel, as they

have very much reduced the importance of the stage—but that there will arise

writing that will retain the principles of dramatic structure of the novel,

but, not having human beings for its characters, will not be producible in the

pictures, and will survive independently. Maybe I am a pioneer in a new writing

that instead of old-fashioned heroes and villains, will have floods and bugs

and stars and earthquakes for its characters and motifs.

Fort doesn’t mention long-dead movie theatres as potential

protagonists, but if he had the above description would apply perfectly to Gary

Rhodes’ The Perils of Moviegoing in

America.

On a synchronistic level, it’s interesting to note that I

finished reading Perils only a few

days before July 20, 2012, the night James Holmes went on an inexplicable

rampage and shot up a theatre audience in Aurora,

Colorado during a screening of

Christopher Nolan’s film The Dark Knights

Rises. This shooting resulted in the

deaths of twelve people and the wounding of fifty-eight others. Only a few days after this tragic massacre,

ultra-right-wing radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh went on the air and blamed

the entire affair not on guns but on Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman film and the “dystopian” negativity rampant in American

media and culture. Since I had just read

Rhodes’ book, however, I knew full well that

theatre shootings extend at least as far back as the 1920s, long before Tim

Burton’s parents were even born. Oh, well.

So much for modern culture being to blame. (Say, maybe it is the guns after all….)

The second book under discussion today is Stephen R.

Bissette’s TEEN ANGELS & NEW MUTANTS (Black Coat Press, 2011), the most

comprehensive analysis ever published of any single graphic novel—in this case,

Rick Veitch’s Brat Pack (King Hell

Press, 1990-91), the main characters of which are a homosexual superhero named

Midnight Mink and his underage protégé, Chippy, and a steroid-popping white

supremacist vigilante named Judge Jury and his underage sidekick, Kid Vicious. Bissette’s analysis is well over double the length of the graphic novel

that spawned it. With seeming

effortlessness, over the course of 400-plus pages, Bissette weaves a complex

web of connections among such disparate subjects as pulp fiction, pornography,

junkbond culture, subliminal sex, the Mickey Mouse Club, skateboarding, two-fisted

zombies, real life mutants, Francisco de Goya, Arthur Rimbaud, Elvis Presley, 1980s

teen comedy stars (“teen meat,” as Bissette refers to them), Dr. Fredric

Wertham and his 1950s anti-comic-book campaign, Michael Jackson, the general

exploitation of children, Make Room For

Daddy, and the death of Superman—and that’s just scratching the surface.

Of special note here are Chapters 3 and 6. Chapter 3 (“W-Wertham was—RIGHT!”) and Chapter 6 (“Up From the Deep”) both focus on the career of psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham, author of the

infamous 1954 book Seduction of the

Innocent, which stirred up a wave of anti-comics hysteria in the 1950s that

directly led to a U.S. Congressional inquiry into the effects of crime and

horror comics on the minds of American children. These two chapters are worth the price of

admission alone. I’ve read a great deal

about Fredric Wertham and Seduction of

the Innocent over the years, but Bissette’s analysis of what Wertham was

actually attempting to accomplish with his work is the most illuminating and

thorough I’ve ever come across.

Anyone interested in the history of comic books, the

increasing influence of mega-corporations on the minds of children, the impact

of societal taboos on popular entertainment, the deleterious cultural effects

of censorship (self-imposed or otherwise), and the art and commerce of killing

underage sidekicks, needs to read Stephen R. Bissette’s Teen Angels & New Mutants.

Without a doubt, this book raises the bar for the scholarship of what

Will Eisner called “sequential art.”